A.3. Article: History of Dieselpunk

The following was written in three parts by Mr. Piecraft and published in Issues 3-5 of the Gatehouse Gazette

Part I: Proto-Diesel

Originally published in Gatehouse Gazette 3 (November 2008)

In order to begin analyzing dieselpunk as a serious genre within the literary world of fiction, it is necessary to realize its development from steampunk as well as cyberpunk, both to which dieselpunk owes a lot, as well as from pulp comics and literature published throughout the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s. The term that was first coined by Lewis Pollak to describe the fantastical setting of his Children of the Sun became a definitive choice word to encapsulate a form of science fiction that starts with the end of the Roaring Twenties through to the beginning of the Cold War, culminating primarily with the Red Scare of the era and its dread of a nuclear Third World War.

This newfound genre gained further notoriety on the Internet among fans of pulp-orientated literature and buffs of neo-noir cinema. Elements from both enhanced the genre’s anachronistic setting within a realm that combined the advanced and somewhat dystopian aspect of the 1930s with an overabundant use of Art Deco and Futurist outlook in style and design. Yet even nowadays the term has hardly been recognized by peers of science fiction — unlike steampunk and cyberpunk, because dieselpunk has yet to officially spawn more original material than the Children of the Sun role-play.

What I seek to demonstrate in this article is how the “idea” of the dieselpunk setting has long existed within fiction; much like its predecessor steampunk. It were the visionary imaginations of Jules Verne and H.G. Wells that inspired steampunk’s purpose in a post-modernist literary world crying out for nostalgic revival supplemented with a touch of cynical worldviews. Steampunk grew in the ranks of seminal, alternative fiction over time, yet has remained very much true to the conscious mind of readers and writers of the fantastic adventure genre of the turn-of-the-century — a genre that, until now, had no proper name. And much like the predecessors and purveyors of steampunk discussed a future of steam powered technology and optimism and adventure during the sometimes crisis and despair of the Victorian era, so dieselpunk, also, will become accepted eventually in the same respect.

Notable precursors to the dieselpunk genre encompass the very same themes and ideas expressed in steampunk — transposed into the 1930s. We find a tumultuous time in which society has not recovered entirely from the horrific experiences of the Great War, yet one in which the threat of another war seems ever present. It is also a time in which the dirtier and grittier aspects of an advanced technocratic society become apparent and accepted.

There are two significant works of period fiction, very different in story and scope, which together perfectly demonstrate the converging dichotomy found in the dieselpunk world of the Interbellum — the period that forms perhaps the definitive setting for dieselpunk fiction.

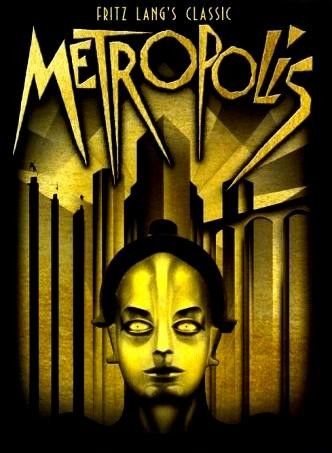

Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1929), although set in a distant future, beyond the typical timeframe of dieselpunk, makes for an excellent example of the genre’s style and technology as prevalent in a future dystopian society: large factories, big pumping machinery and other forms of radical technology and science that at the time of the film’s making were but pure fantasy, emphasized by German Expressionism. The design and setting of the cityscape represent the Futurist style of the dieselpunk setting. Altogether, Metropolis perfectly exemplifies the “Piecraftian” dieselpunk, one that predicts the darker and despairing outcome of a world changing event, be it a war or cataclysm. In this case we recognize that Lang seeks to show us the dire consequences of a war out of which a totalitarian regime emerges victorious. This brings about a world in which the freedom and happiness of the masses are compensated in order to stabilize peace.

Man With A Movie Camera (1929), directed by Dziga Vertov, is a depiction of the urban-industrial life in the Soviet-Russia of the 1920s. The film represents a vision of progression as it portrays the enthusiasms and hopes of a society emerging from a worn and weary past and now confident about its future. Citizens are shown at work and at play, interacting with the machinery of their modern world. The visuals possess a raw element of experimentation, involving stop-motion animation as well as montage to evoke the spirit of the times, and cast an entirely idealistic outlook of society in Odessa and other Soviet cities upon the rest of the of the world.

Vertov portrays his story in a quasi-observational documentary style, even incorporating elements of propaganda filmmaking to the simplistic narrative. To the extent that it can be said to have “characters,” the film interacts with the perspectives conveyed by the allusive Cameraman of the title, and the modern Soviet Union he discovers and presents in the film. This example perfectly fits the “Ottensian” dieselpunk as a hopeful and excited view of the modern world that emerges from the ashes and suffering of the past and is invigorated by the radical advances of technology and science.

Although the two films are completely different and were never intended to be considered dieselpunk, their imagery and themes have inadvertently influenced dieselpunk culture. Metropolis is a film that questions technocratic and societal class issues within the frame of science fiction. The unique style of German Expressionist mise-en-scene evokes the fantastical and seems to place the events of the film beyond any time we could possibly relate to. However, it is the underlining story which harkens our consciousness to the issues of totalitarianism and class struggle — which were ironically carried through to the 1930s up until the 1960s when civil liberties were finally recognized for every man and woman. The film was made in 1929 before the Second World War, but was perhaps reverberating the effects of the Great War that were still fresh in the minds and had left scars on many around the world.

Man With A Movie Camera was made in the same time as Metropolis, yet with a very different purpose: to document life under Communism. A new world was opened to Russian eyes after the Revolution; people were no longer struggling to live, for everyone was considered an equal in Lenin’s state. The film represents confidence in a social system that was still in its early stages at the time. Through it, we garner an optimism about a future which seems to have no bounds; one is excited by the great improvements made to society, by the pushing of boundaries of a strong industrial nation that is exploring new concepts and ideas about technology and society, and also a nation that perpetually oils the gears of the Machine-State that will lead it to greater heights. Unlike Metropolis, Man With A Movie Camera promotes an enthusiasm that people were not to dwell morbidly on the war and regime of the past, but that they would improve their situation by working harder and moving faster and further to unknown reaches for the benefit of all involved.

What makes Metropolis and Man With A Movie Camera precursors to the genre? Not only do they evoke the experience of the era in which dieselpunk is set; they also promote two very different ideals which were fictionally drenched in fast-forward thinking dreams for science and society — both with an important socio-political message. Both films illustrate the new and the upcoming technologies of the Interbellum, for at the end of every war breakthroughs in science are brought to public awareness. A race for arms and the previously unexplored carried on even into the Second World War and the Cold War; and with it came the increasing production of consumer products, be they automobiles, telecommunications or fashion. So it is acceptable to acknowledge that throughout the 1930s, ’40s and early-1950s the world was constantly changing politically and technologically, spawning new advances in culture and science. This highly unstable period that was in a flux of progressing toward greater power in both a technologic as well as a political aspect, brought about many great social crises and awakenings, reinforced of course in the very films which were at the time prophetic in their own analyses of the times.

But because neither film embodies dieselpunk absolutely, they can only be seen as precursors to the genre. They can be considered as strong influences to the genre, just as Jules Verne and H.G. Wells relate to steampunk and George Orwell’s 1984 and Jean-Luc Godard’s Alphaville to cyberpunk. And just as in steampunk and cyberpunk, many of the themes and designs and imagery found in these films, have been adopted into the dieselpunk setting, influencing other works which have become generally accepted over time as existing within the known genre.

Part II: Diesel Classics

Originally published in Gatehouse Gazette 4 (January 2009)

With Hollywood reverting back into its archives for added inspiration for narrative ideas, we find a recent trend of nostalgic hindsight to the age of the Roaring Twenties and the 1930s. This seems to have infiltrated gradually the science fiction genre that is emerging in contemporary cinema. Films like Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow (2004) and The Mutant Chronicles (2008) have perhaps inspired the intrigue in the early first half of the last century. Other recent films like Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008) and The Spirit (2008) have sparked new interest in the previous century, overcast with economic turmoil, lawlessness on the streets and in politics and the ever present dystopian sentiment towards a near-hopeful future with the potential of war hanging in the balance.

We must also not forget the alternative historical elements of the times, when people perceived a future that could at one time or another have been dominated by the totalitarian powers, specifically the Nazi regime — evoking concepts of the supernatural and Über-technology that was revolutionized by the whacky radicalism of engineers and scientists of the time. Such themes promoted in the independent feature Iron Sky — which alludes to what would have happened if the Nazis had escaped to the Moon — present the growing fascination with the emerging genre of dieselpunk.

Referring back to the understanding of dieselpunk, it could be said that what once was a mere neologism to define a type of alternative history science fiction that was all too obsessed with the ongoings of the 1940s, has slowly integrated into the public consciousness. Increased with the added support of films that harken back to this time period, a gradual and easier environment for dieselpunk has become accepted by the masses of steampunk and cyberpunk aficionados as a reputable and notable term and genre.

The following is an analysis of particular “quintessential” works of fiction that correlate what make up the understanding of dieselpunk — or at the very least examples that reflect the genre in contemporary media today. There has been considerable debate relating to the subject matter of how a piece of fiction would be considered as dieselpunk. The examples given have been linked to the genre in regards to the themes and the setting by which they take place in. Each example possesses particular elements that confirm their position as a genre work of fiction within the universe of dieselpunk.

What follows is an analysis of “Ottensian” and “Piecraftian dieselpunk,” followed by a few examples each from various contemporary films that illustrate how the genre is recognizant in terms of its thematic context from the choices selected.

To begin, we shall venture into the realm of “Ottensian dieselpunk,” bringing with it elements of the hopeful perspective correlated to the technology and times of the prolonged 1930s era. Most films that possess the “Ottensian” setting, place the importance on a world which has developed from the destitute ashes of a previous conflict or dire event (i.e., the First World War of the Great Depression) leading to a much more positive outlook.

Just Imagine (1930), directed by David Butler, put forward the tagline “YOUTH AND LOVE 50 YEARS FROM NOW!” on its original printed ad. This reminds us of F.T. Marinetti’s blossoming Futurist Art Movement of 1919, promoting ideals of modernity, embracing technology by a passionate, younger generation to dispel the boring and mythic qualities of the older deprecated and dated systems and culture in substitution for one that looked ahead to a newfound future, full of aspiring potential and dynamism.

Butler depicts a New York City in the 1980s where airplanes have replaced the automobile, people’s names have been replaced by number codes, and pills have replaced every day food — heralding a retro-futuristic nod to the later animated series The Jetsons of Hannah-Barbera.

Just Imagine deals with the detachment of humanistic love by emphasizing the control the corporate state has over pre-arranged marriages which has replaced the romantic ideal of true love, and test-tube babies replacing the intimate act of reproduction. The story revolves around a man who is struck by lightening and revived by scientists. His name is relabeled as Single-O. Single-O then goes on to befriend and fall in love with a girl known as J-21, only he cannot marry her because he is not “distinguished” enough. The film follows Single-O’s escape to elope with J-21 on an expedition to Mars by a renegade scientist.

As fantastical as Butler’s film is, it illustrates the hopeful sentiment of the time through the technology that the visuals elaborate on — even with the naive and outlandish portrayal of the Martian landscapes. Therein we find the suitable role of the anti-heroic protagonist in Single-O who due to the worldly circumstances of the times cannot attain his happiness, and therefore must go on the run from the control of the government and seek refuge. Even though the film is set in the 1980s there is a clear indication that the narrative focuses on the reverberations of a world that has endured a cataclysmic global war, thus requiring some novel ideology in order to sustain the new order.

Therefore many of the older values and morals are still being employed. An example of such values is reiterated with the way the film places importance on class, bringing about Single-O’s preoccupation of not being “distinguished” in society. Or perhaps the end process of the war would lead the viewer to believe that the victors were in effect the totalitarian and authoritarian powers and the world of Just Imagine is merely a glimpse of a near bleak but technologically superficial future.

Just Imagine brings into awareness the same ideas portrayed in other “Dystopian Piecraftian” examples, such as those found in the precursor to cyberpunk: George Orwell’s excellent literary statement on a world gone horribly wrong when taken over by the malignant powers of corporate rule in Ninteen-Eighty-Four as well as Terry Gilliam’s satirical film homage to Orwell’s piece, Brazil (1985). And last but not least the “Dark Ottensian” example, Kazuaki Kiriya’s visual interpretation of Dai Sato’s romanticized mega-mecha world of Casshern (1973-74). All four films feature the conceptual design elements of a world that has its mind deeply involved in the nostalgia of the past — specifically the 1930s and onwards throughout the Interbellum war period of World War II.

These films equally address the qualities of a retro-futuristic landscape influenced by political ideology (regardless whether it is an overly industrial-based capitalist system or wholly totalitarian regime) throughout most of the early-twentieth century. This is a vision of an atomically charged future where technology has become the opiate to the masses, especially in regards to engineering and design. We find airplanes or airships as the foremost modes of transportation; the sky in seemingly perpetual darkness from the smog of combustible vehicles; dirty diesel guzzling locomotives and the petroleum-producing factories dotted across the metropolis-complex. All these elements make up the definitive dieselpunk world.

We find elements of the “Hopeful Ottensian” mostly dominating the consensus of dieselpunk fiction — predominantly focusing on the mood leading up from the Great Depression that either is on the verge of sustaining itself or having never occurred. This example promotes a worldview that is still at its peak from the Jazz Age that brought about radical developments in technology on every level of urban life, a cultural upheaval that added to the greater adventurous outlook of the new generation as well as expanding the horizons in which to enrich the narrative of a newfound empowered world.

Examples of these hopeful and changing times are mostly evident in the popular depictions of pulp-orientated narratives found in The Rocketeer (1991), Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow as well as Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull. In all three examples we find a protagonist that represents the qualities of the heroic spirit of the times: a strong sense of morality with a cynical mind-set to the world around him attributable to some past personal conflict. Such values are defined by the strive to seek a resolution to the perpetuating crises that have developed in the world. Most notably the Nazis are seen to be the root of all worldly woes, as exemplified in the Indiana Jones series, The Rocketeer, Hellboy (1991), the video game Return to Castle Wolfenstein (2001) and even Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow.

The “Ottensian dieselpunk” narrative is dominated with this characterization of a strong, male heroic protagonist — an adventurer at heart, fearless, yet very human still. The rugged and tough exterior is the stock for most pulp-orientated heroes of the time. However there is a deeper quality to the dieselpunk hero as the protagonist reflects the world which he has lived in.

We see in all examples a world dominated by the petroleum fueled anxiety of governments, the emphasis of modernity pushing the envelope further.

In Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989) there is the memorable scene of the zeppelin providing a modern form of transportation in a modern time. Whereas in Sky Captain we are introduced to Dr Totenkopf’s modern day colossuses (giant mechanical flying robots) and once again to the zeppelin, only this time docking at the Empire State Building.

This is also present in The Rocketeer, where the giveaway is in the remarkable rocket pack that provides the protagonist Cliff with his ability to fly. All these differing mechanical wonders and advances in mega-tech are a throwback to the curious and grandiose ideals of technology and machinery presented during the 1930s and reinforced throughout all three films with the retro-futuristic Space Age style and design in architecture and fashion.

These aspects of the world presenting modern change and radical advances in different areas of society such as tourism and transportation are what attribute to a blossoming future for the “Hopeful Ottensian” world. Even with the overbearing presence of the Axis in the Indiana Jones series or The Rocketeer there is the plausible utopian scenario as presented in Sky Captain where the Nazis settled the war with the Allied Powers through a peace treaty instead. Of course the necessity for the Nazis to either be portrayed as good or evil is irrelevant to a “Hopeful Ottensian” world as is clearly seen with Sky Captain‘s Dr Totenkopf. What remains is the feeling that even in an uncertain world of ongoing war there is the excitement of things changing; a sentiment that was celebrated by the likes of the Futurists in the early twentieth century who promoted dynamism, speed and violent regime change.

The possibility of victory is the essential ingredient to films as Indiana Jones, The Rocketeer, Sky Captain and The Iron Giant (1999) where the world weary hero overcomes the malignant, at times dated supernatural forces originating from the Old World — such as the archaic and mythic roots to the totalitarian regimes of the time. If such forces were to succeed, they would enforce an evolved technocratic yet compartmentalized regime; the future platform for the “Dystopian Piecraftian” setting.

In the “Dystopian Piecraftian” we find the ambition and excitement no longer existing in the world. Instead, an expression of despondency and despair lingers upon society which has long forgotten the novelty or dynamism of the old glory days of the Jazz Age. Creativity and innovation is exchanged for productivity and submission, and we find this all too true with the substitution of the heroic protagonist into antiheroic. Whereas the “Ottensian” hero reflected the traits of a steampunk identity of adventure and ingenuity, the “Piecraftian” character projects a more cyberpunk antihero sentimentality, one of hopelessness, deep cynicism, sarcasm and personal turmoil in accepting his circumstances, due to a random event that has marked a considerable change in his monotonous lifestyle.

This is seen with the likes of Sam Lowry from Terry Gilliam’s Brazil who can only dream of being the liberated romantic hero within his imagination that cries out to break through the bureaucratic, Orwellian state surrounding him. We also find that this lack of motivation leads to a sense of duty being of the utmost importance to the “Piecraftian” antihero. Lowry is at first extremely dedicated to his routine, albeit with reservation but eventually out of his own internal curiosity realizes the truth about the system he works and lives under. Lowry then becomes an enemy of the state inadvertently out of his own sense of individuality, breaking free from the herd.

The same could be said of SS-Sturmbannfuhrer Xavier March from Robert Harris’ Fatherland (1992), who out of his duty as a homicide police officer of the New European Reich (the Germans having won the war) begins to investigate the mysterious death of a Nazi Party official. A coverup of the Holocaust is subsequently uncovered. With the assistance of an American journalist, March probes deeper and discovers the full truth about what happened to the Jews; a truth that could destroy the delicate peace process between the New Reich and the United States. In his attempt to evade capture from the Gestapo we find March like Sam Lowry, questioning his position within society and his allegiance to the system he functions within all the while fighting against it.

The characters of Sky Captain and The Rocketeer are the new hope with a “can do” attitude for a generation in a time of turmoil. They are not deliberately demonized by the ruling power, rather they are idolized, as is customary with the heroes of pulp literature and Golden Age comics. A “Piecraftian” hero is more likely to succumb to a world darkened by the technology and attitudes determined by the outcome of the Second or a Third World War.

Comedy comes natural within most narratives of the “Hopeful Ottensian” setting due to its less complicated and laissez-faire attitude to the burgeoning mechanized world that is constantly moving forward. This brings about a good natured and excitable outlook of the world, with witty and sarcastic remarks being the usual fare from the “Ottensian” hero or with the addition of a sidekick for comedic value as is seen with the examples of Shortround in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984).

In the “Dystopian Piecraftian” setting we find rather than comedy or slapstick being the norm, satire takes precedence instead. This is evident with films as Brazil where social commentary becomes the focal point of the tour de force behind the development of the narrative. We similarly find the same satirical demonstration in Andrei Tarkovsky’s seminal movie, Stalker (1979). The premise referencing the consequences of a nuclear apocalypse; The Zone, a no man’s land near an anonymous unnamed city; an alien place guarded by barbed wire and soldiers. Over his wife’s numerous objections, a man rises in the dead of night: he is a stalker, one of a handful who have the mental gifts (and who risk imprisonment) to lead people into The Zone to the Room, a place where one’s secret hopes come true. That night, he takes two people into The Zone: a burnt out author, cynical, and questioning his own literary genius, and a mild mannered scientist more concerned about his knapsack than the journey. In the deserted Zone, the approach to the Room must be indirect. As they draw near, the rules seem to change and the Stalker faces a crisis. There is an exaggeration of the world caricaturizing it somewhat, however still retaining the serious tone of the dystopian atmosphere that pervades throughout.

Finally, the darker spectrum of the “Piecraftian” and “Ottensian” presents a world which leaves the emphasis of the political or symbolic nature of the world to a much more irrational or futurist outlook. In the “Dark Ottensian” there is a melancholic atmosphere projected within the world, where the dark pillars of petroleum fumes and engine noises and vehicles no longer bring about sentiments of joyous anxiety and wonder but one of conformity and pollution. Casshern, The Mutant Chronicles (2008) and Delicatessen (1991) each portray a world that harbors the mood of the previous decade. The angst and depravity still remains from the previous economic crisis and the futility of the last war still resonates upon the characters in this new world of wondrous mechanical and industrial prowess.

Even with the splendor of the giant mechanical creations as gargantuan robots and skyscrapers and mega-structures, in Casshern there is that horrific reminder of the previous war that is demonstrated with the village scene where we find people living in poverty and dying from starvation — left over from the previous war to rot. Or in the case of The Mutant Chronicles the forgotten ancient, albeit alien machine that is unknowingly unleashed upon the world due to the ongoing wars between the global corporate powers — another reminder of the destructive effect of the machine-industrial complex.

We find the haunting themes of technology and an unresolved past that bring about a much more jaded world that seems to be caught under the shadow of progression rather than brimming with hope and prosperity as seen in the “Hopeful Ottensian” setting. However, even so, Casshern and The Mutant Chronicles as well as Delicatessen provide their dieselpunk world with a hero who attempts to remedy the problems through their own means, even if it relies on their self-destruction — as is usually the case in all three films.

The emphasis on famine and poverty emanating from the social collapse of the Depression and on wartorn urban slums or cities built up entirely of factories and industry are key to the look and feel of the landscape capitalized in all three films and are another important facet to the dieselpunk formula. In the “Piecraftian” world there is no hangover from the previous decade, such as the socio-political problems that have carried on into the consciousness of the new generation.

Mad Max (1979) and Six String Samurai (1998) do not present a particular mood to their world other than one of nihilism where the future is uncertain and the past is only manifested through the physical ruins left behind from the previous civilization. Nostalgia plays no importance upon the characters in the “Post-apocalyptic Piecraftian” dieselpunk setting. This is because they no longer retain any memory of the “Hopeful Ottensian” or “Dystopian Piecraftian” world prior to the “rapture,” only a visual reflection of what it was once like from the objects and landscape that survived. The antihero is reinforced from the “Dystopian Piecraftian,” only in this case we see again the lone stranger attitude revel in the characterization of the protagonist, and fast forwarded to a much more alienated and misunderstood stereotype.

The “Post-apocalyptic Piecraftian” antihero has no sense of responsibility or duty; therefore is carefree and is truly a nihilist. He exists and survives for the present, the antihero is a survivor and can be seen as both heartless and cruel at times or good natured and loyal depending on the circumstances of a situation presented in the narrative. This is exemplified with Buddy’s uncaring and uninterested attitude at first to the abandoned Kid he encounters on his path in Six String Samurai. And this is also true with Max’ personality by the manner in which he treats anyone he encounters in Mad Max. This can be explained because both Buddy and Max have experienced an event in their world which has caused them to distrust their fellow man — a clear differentiation from the always-at-hand and helpful Samaritan of the “Ottensian” hero. Since the “Post-apocalyptic Piecraftian” world is portrayed in anarchic disarray this inadvertently causes the negative-realism of an ultra-industrialized world to affect the characters that exist therein.

The ordered and bleak world that breaks the will of the human spirit, in the setting of the “Dystopian Piecraftian” is exchanged for one where the world is now completely destroyed and the people are an outward expression of a neoprimitivistic future, enhanced by the scrapped and wreckage leftovers from their diesel charged and mechanical machinery that survived the cataclysm.

The present “deprecated” technology and resource of fuel and mechanical sustenance is a drawback to the times before the great technological boom perpetuated by the megalomaniacal obsession and propulsion of the diesel empowered world of the mid twentieth century. This is their only link to the era of the 1930s, that and perhaps the scraps and shreds of clothing that remain, mostly connected to the automobile and motorcycle styles; Greasers, Rockers, mechanic, engineer and industrial work wear as well as army fatigues seem to be the typical clothing of the post-apocalyptic individual. Later we find these technologies reinvigored in a primitivistic and patchwork style (much like their own clothing and state of mind), fused with the rusted remains of a time when such machinery was literally the oil that greased the cogs for the momentum of a futuristic technocratic society — one which would befall the events that take place in the Mad Max series, Diesel (1985), and Spirits of the Air, Gremlins of the Clouds (1989). The destruction of the urban sprawl formed by such technologies and social highs that eventually bring about their own demise promoted in such films as Metropolis (1927) and Tetsuo (1989) which present the future illustrated within a “Post-apocalyptic Piecraftian” landscape.

Dark City (1998), directed by Alex Proyas, is perhaps the epitome of the darker nature of dieselpunk. The film possesses both attributes characterized in the “Piecraftian” perspective of the genre. We find the dark despondency and dystopian world prevalent in “Dystopian Piecraftian,” exemplified by the bureaucratic and ordered society by which the people exist within the constraints of their city, always living in the darkness. A city deeply reminiscent of the 1930s in an attempt to emulate the ethos and essence of the “Hopeful Ottensian” setting. However, we find out later that this city is nothing more than a constructed environment controlled by strange, psychic alien beings known as The Strangers who have saved the remaining survivors of a post-nuclear Earth and now regulate them on a mechanized world formed of gears and combustible engines that work to fabricate the illusion of the world prior to the cataclysm.

The central character once again is the misaligned antihero, John Murdoch, who awakens alone in a hotel to find that he has lost his memory and is wanted for a series of brutal and bizarre murders. While trying to piece together his past, he stumbles upon a fiendish underworld controlled by The Strangers who possess the ability to put people to sleep and alter the city and its inhabitants. Murdoch seeks a way to stop these beings and expose the truth before they capture him and before they can once again assimilate him back into the ordered society.

The city is nothing more than an advanced computer perpetuated by the energy of the people imprisoned within it. The Strangers seek out Murdoch because of the extraordinary powers he manifests while he slowly recollects the memories of his original past. John decides to find out what is happening in the city; he questions the everlasting night and the apparent inability to leave the city. These are all elements of an exaggerated noir-esque environment. The dark, brooding atmosphere, smoky skies and oil-slicked streets are obvious dieselpunk characteristics and like film noir and other pulp material that has inspired the genre, we find that all the action takes place in one setting which is cleverly manifested as the Dark City itself. The individual protagonist never seems to escape the sprawl of the urban metropolis or the world in which the events that pave the way for the changing future.

Perhaps this is the pessimistic perspective by which any punk genre defines itself within the subject material. The characters are locked in a continuous time period, marked by the advances in technology that inspire all aspects of civilization, from architecture to fashion to music, yet they can never release themselves from that ever changing fate of the future. A future that is persistent with the nature of the setting of the world, thus why Indiana Jones and Sky Captain will always remain the same, unchanged whilst Max and Murdoch must sustain the persistent downfall of their own bleak future.

Part III: Diesel’s Punk

Originally published in Gatehouse Gazette 5 (March 2009)

Punk is not a synonym for era; rather the era is defined by the prevalent technology ever present in the context of a science fiction world. In actuality there is confusion in regards to the differentiation largely of a literary (prevalent in cinema, games and literature) understanding of pulp fiction, alternative history as well as modern steampunk with the genre of dieselpunk. It must be understood that dieselpunk has borrowed and is influenced by elements from all three — which creates the entity that is dieselpunk as understood today.

From steampunk it becomes inspired by the derivative mindset originally outlined by the amoeba that is cyberpunk of an antihero characterization within a troubled world that is most often reflected through the dystopian or at times abstract utopian values of an advanced technocratic world. This idea although a brief glimpse of all the facets to which cyberpunk as well as its many counterparts divulge on, make up the integrity of its science fiction.

Pulp literature seemingly comparable, focuses on the early 1930s tradition of promoting the iconic times with adventures experienced through the eyes of pulp heroes: characters who represented the prominent ideals of courage, a “macho” or strong-willed and fearless masculine personality (even inherent among feminine pulp heroes) and daring qualities that people dreamt of in their nation’s heroes.

Therefore we observe that dieselpunk is a constituent of both steampunk and the pulp style of literature and can be considered another counterpart of the literary “punk” derivative from cyberpunk.

Dieselpunk combines the antihero entity that is modified within steampunk’s “Great White Colonial Explorer” (i.e., Allan Quatermain) archetype or “Daring Adventurer” (i.e., Doc Savage) — which were originally derived from cyberpunk heroes — back to the “Misaligned Urban Detective” (Sam Spade), “Military Hero” (Biggles), “Adventurer” (Indiana Jones) or “Outcast” (Mad Max), who posses a stronger hold on moral values and works toward the ultimate good of his people, even though he is plagued by the darkened atmosphere of his time. There is also a dash of alternate history; not only in regards to the outcomes of the Depression and World War II, but throughout the period dieselpunk is inspired by, being the 1930s and onwards.

Altogether dieselpunk should no longer be understood as simply a spinoff from either of these earlier literary genres. Instead it could be argued that each of these genres reside under an umbrella that incorporates or influences all styles from each, sometimes from one, which is where the confusion spurns from.

Perhaps it is best to accept that the “punk” suffix added to these literary genres developed not out of the same sense as the punk musical scene, but out of the actual definition of the term. Punk referred to a label given to antagonize anyone who was seen as rebellious or anti-establishment; mostly designated to the younger generation, basically one who would go against the grain of society. This “punk” attitude was further enhanced with cyberpunk in an all too bleak view of the 1980s drowned in the Digital Age and mass consumerism, but it was later carried into the extraordinary adventures and inventions found in a curious age before the turn-of-the-century. An age that reveled in the world of steampunk, with high hopes about industry and progress, bringing about exciting technology but also social change. Thus the daring adventurers and anti-social inventors of this time could be seen as the “punks” of their period, rejecting the status quo of the time to challenge and seek their true destinies. We observe that this was further enhanced by the inclusion of the urban, gritty and raw characters found in the 1930s, demonstrated through film noir and pulp literature.

The hero, whether one bearing an optimistic or pessimistic perspective, will always encounter the side effects of the society they live in — we most commonly find this to be true with works of fiction taking place during World War II — caught up in sometimes despairing circumstances.

Therefore the understanding of the term dieselpunk refers to a form of literary science fiction that takes place during a timespan in which petroleum fuels machines while the atomic and combustibles are at its high point; just as steam locomotives and steam- and gas engineered machines are quintessential to steampunk. It is an ambiguous and yet general aspect of the neologism that comprises the “punk” attitude or element of the strange, the “otherness” in juxtaposition to the type of society or world in which the adventure and stories take place.

Dieselpunk technology exudes an aim to express the energetic, dynamic and violent quality of contemporary life, especially as embodied in the motion and force of modern machinery. And therefore one can see a darker side to this romanticism that has dropped since the previous era.